We are lucky to work with many amazing people at HRI. Clarissa, our Head of Donor Services, was born with complex congenital heart disease. She is a warrior and an inspiration. This is her story, in her own words and in the words of her loved ones.

Clarissa:

My name is Clarissa. I’m 43 years old and a twin.

I’ve always thought of myself as a fighter. Not someone who picks a fight, but someone who has been fighting for my life since the day I was born.

I was born with a congenital heart condition (CHD). I have atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect and left superior vena cava. And yes, it’s a mouthful. I’ve had two open heart surgeries, three ablations and multiple catheters.

I’ve also got an issue with my liver – a haemangiona that ruptured three years ago. My dad was told I would have died if I hadn’t been at hospital by chance when it happened. I ended up in the ICU for a month. I also don’t have a portal vein.

Every time I have a scan, I’m met with astonishment. “Wow, your anatomy is so unique." "You’re a medical mystery,” is another phrase I hear a lot. They can’t understand what my body is doing or how I’m still standing.

Having a heart condition hasn’t defined me or shaped my life in any way. I have still been able to have a fulfilling life and have accomplished so many things along the way.

Growing up I knew I was lucky to be alive.

I was born when treatment for heart disease wasn't as advanced as it is today, and therefore finding out my diagnoses wasn't an easy process for my parents.

I was always told by my grandma: “You are lucky to be here; and we are so lucky to have you.”

Obviously, I have no memory of it but I often think about what my parents had to go through when I was a baby.

Clarissa’s parents, Sandra and Spero:

I only found out I was having twins quite late in my pregnancy. Both the girls were tiny. In fact, from the time I was delivered the surprise news until the day they were born, Clarissa didn’t grow at all.

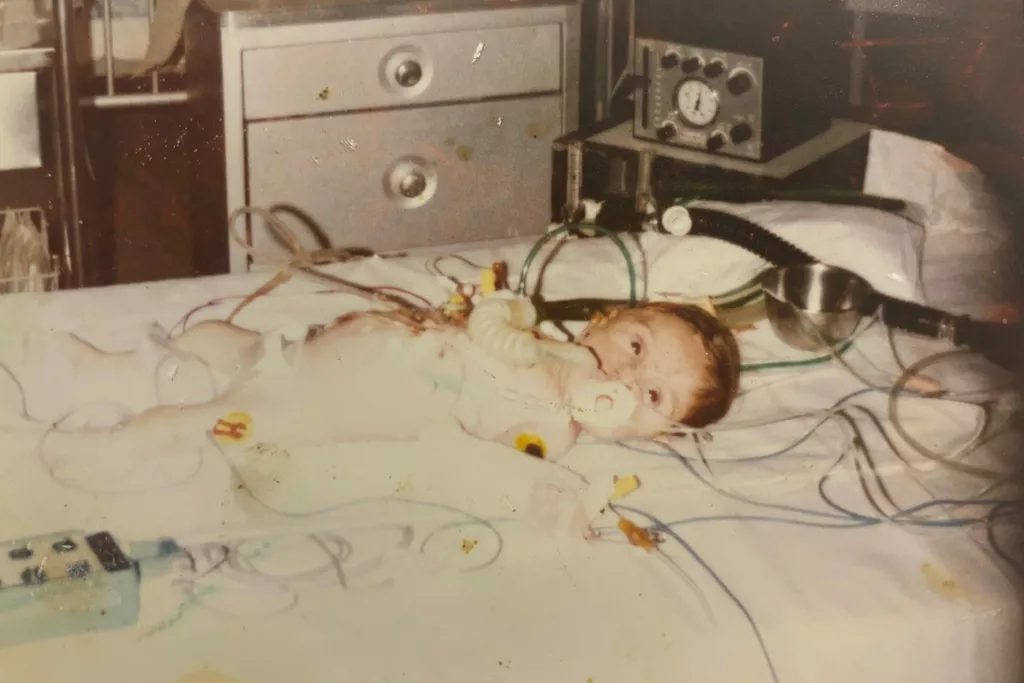

She arrived into the world weighing just 1.9 kgs and was whisked straight off to NICU. They both were. I knew something wasn’t right straight away. Clarissa wasn’t breathing properly.

But as it turned out, she was actually in heart failure.

Clarissa didn’t grow. She wasn’t feeding well and didn’t put on weight. But doctors didn’t know what was wrong with her. No one could figure out what was going on.

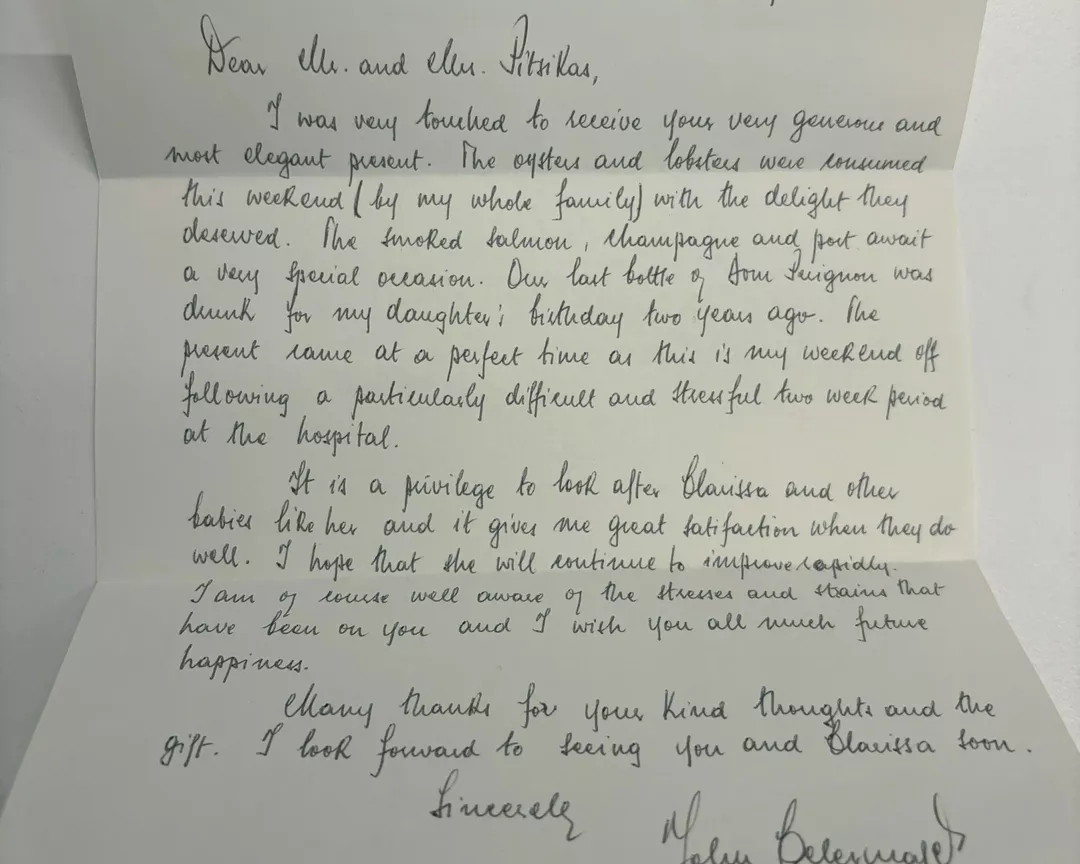

Finally, when Clarissa was six months old we got an appointment to see Dr John Celermajer. And that’s when we got a diagnosis. He told us she had two major problems with her heart – two holes and her veins were in reverse.

We were absolutely devastated. And very distraught.

Clarissa's parents spent the first year in and out of hospital with her

That first year we spent in and out of doctors' offices and hospitals. It was gut-wrenching because you would make friends with other parents and then the next time you went in, the baby was no longer there.

Clarissa had her first open heart surgery when she was six months old. She had to be 2.7 kgs so was fed a special type of formula to help her put on weight.

She stopped breathing three days after the surgery. We were told she had a 95 per cent chance of surviving the surgery. And it wasn’t just her heart that was affected. She had issues with other parts of her body, too.

However, Clarissa was also not a textbook case and we were told she would likely need further corrective surgery. She ended up having a second open heart surgery when she was 13.

Even after the first surgery Clarissa was very thin. And she was delayed in everything she did. She never learnt to crawl. She ‘bottom scooted’ everywhere. And she had to go to physio to learn to walk. Her legs were so small they couldn’t support her body properly.

We are so very proud of Clarissa. She is our little miracle.

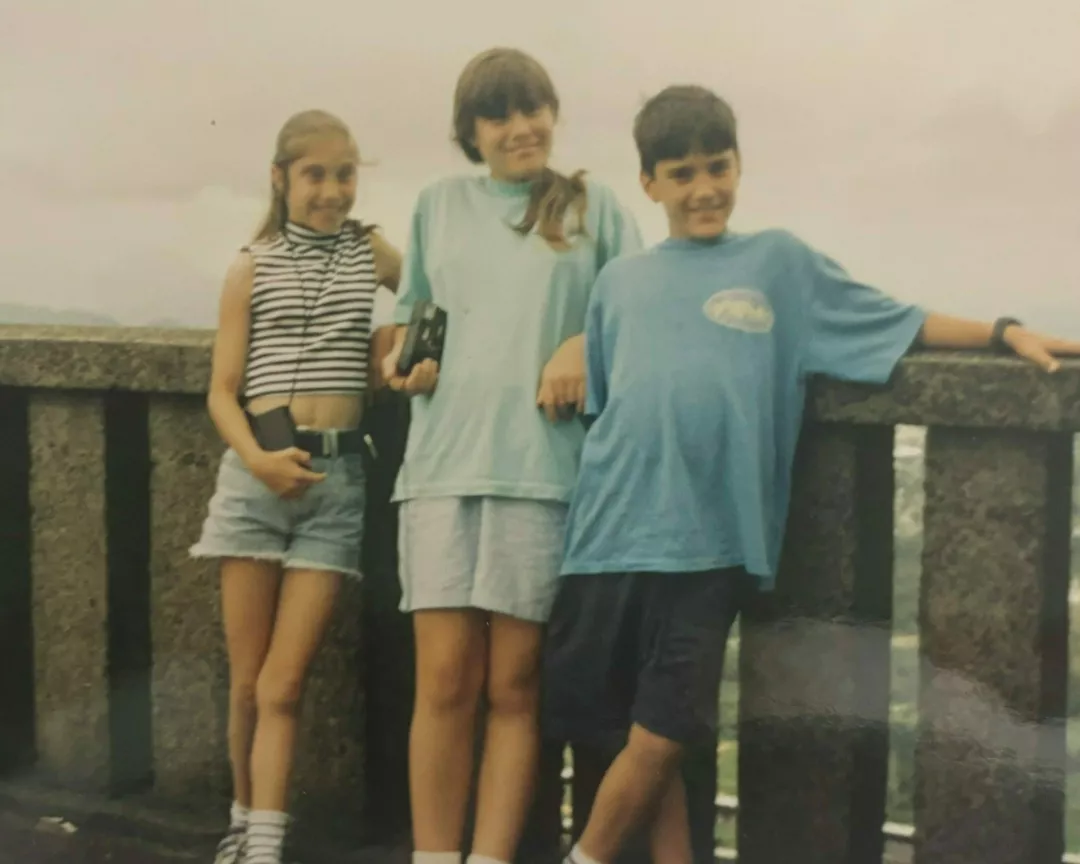

Clarissa and her family

Clarissa:

Throughout my adulthood I was completely healthy, with no real complications, although I continued to have yearly check-ups.

It wasn’t until one night after coming back from a walk with my dog, Kye, I felt strange. I felt like everything was closing in on me. I had pain in my left arm, my throat felt like it was closing up, and I felt like my heart was about to explode.

I brushed it off and went to bed, but I couldn't sleep.

So I called my parents, who rushed over, took one look at me and called an ambulance.

That was my first episode of super ventricular tachycardia (SVT).

I was told it would happen again – I felt like I had ticking time bomb inside of me and was constantly on edge. It continued to happen every six weeks for probably a six-month period then after that I was fine. I put it down to stress, and lots going on personally and professionally, and thought that was the end of it.

Fast forward six years and after a trip to Thailand, I felt exhausted all the time. I could hardly walk without being out of breath. I knew something wasn’t right, but thought I would wait to see my cardiologist in June.

However, when I discovered that he had retired and that my appointment would be with someone else, I panicked. I didn’t want someone new, who knew nothing about me or my complex heart condition, so I contacted Prof David Celermajer.

During a work seminar at HRI 10 months earlier, I had thanked David for his continued work and for following in his late father’s footsteps, who had diagnosed me as a newborn. I said to David that maybe one day he can finish off what his father had started, but never in a million years did I think that he would take me on as a patient so soon.

Since seeing David I’ve had the most exceptional care and treatment. He is kind and understanding and always available. By the end of my first appointment he put me straight into hospital and said that I had been in and out of a dangerous heart rhythm (240 beats per minute) since January.

He also arranged for Prof Mark McGuire to carry out the ablations I needed, who has also made himself available, when necessary, at short notice and devoted a great deal of his time and expertise to try and resolve my issues with the SVT.

I’m so thankful to be in the best possible hands.

Clarissa with family in Thailand (left) and the letter from Dr John Celermajer (right)

Clarissa’s cardiologist, Prof David Celermajer:

It’s a joy to look after former patients of my dad. Clarissa’s father brought me a handwritten note from my father to show me. As my father died quite young, many years ago, that was very meaningful for me.

Helping young adults at their moments of need is a great privilege. Most, Iike Clarissa, are brave and resilient.

I am very grateful to be in a position to try to help them.

Clarissa:

I started working for HRI about two years ago.

I love that I am working for an organisation that is helping to raise awareness for conditions like CHD. I want all those people that are currently battling CHD and heart disease to know that they aren’t alone.

It’s amazing knowing that I’m working for a company that does all this amazing research – and that it’s going to help people like me. The advancements are incredible.

I want to thank my parents for all that they have done for me. They have always dropped everything to help and support me.

My biggest worry now is David telling me that I'lI need to have another open heart surgery.

Thankfully, I have been OK the last few months. I am monitored regularly and take medication to keep my blood pressure down.

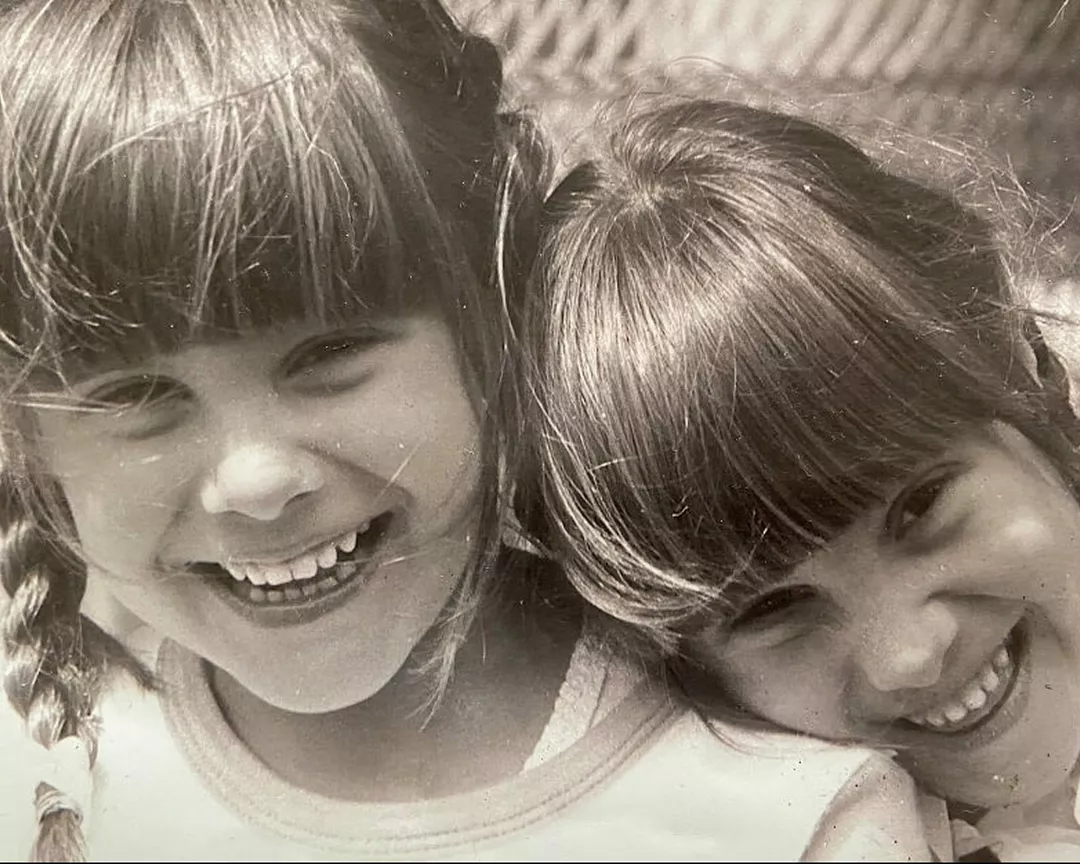

Clarissa’s twin sister, Evana:

Four minutes. It's crazy to think how such a short amount of time could shape so much of my life. Being the older twin, the healthier one, the stronger one – those four minutes somehow feel like they've defined a big part of who I am.

Growing up, things were a bit different for me than for most kids. Because I had a twin sister who's been dealing with a congenital heart condition since birth.

I've often wondered if me being born first had anything to do with it. Did something happen while we were both in our mother’s womb? Was it because I was bigger and stronger? Did I hog all the nutrients? Questions like these stir up a real mix of emotions – concern, guilt, a sense of responsibility, and a whole lot of admiration.

Watching Clarissa go through endless doctor visits, tests and surgeries was never easy. It was tough as a kid, and it's just as tough now that we're adults. Seeing her face those health challenges head-on always leaves me feeling a little helpless.

Life with Clarissa is never straightforward. It's always one unexpected twist after another. Like that time she went in for a foot surgery and ended up in the ICU because of her liver. With her, you learn to expect the unexpected, especially when it comes to her health.

Feeling guilty comes with the territory too. Why did she have to deal with all of this and not me? Because of her illness, she missed out on a lot of school, which meant I ended up being the "smarter" one, the "stronger" one, the one who had an advantage both academically and at sports. And while I knew it wasn't a competition, I sometimes found myself holding back, feeling bad for having it easier.

Being the healthier twin, I've always felt this sense of responsibility. It was my responsibility to look out for her, to support her and to stand up for her when anyone gave her a hard time. But I never had to think twice about it because our bond is unlike anything else. It's stronger than if we were just regular siblings.

But above all those feelings, there's this overwhelming sense of admiration. Clarissa's resilience is something else. The way she handles her condition with such grace makes me unbelievably proud. She doesn't even realise how strong she is, how much harder she's had to work just to be where she is today.

With all the obstacles she's faced, she's like a walking miracle to me. How lucky am I to have been by her side through it all. How lucky am I to call her my twin.

How is HRI helping?

The Clinical Research Group is working on several exciting projects that will help to transform – and save – the lives of people with congenital heart disease (CHD).

With the Congenital Heart Alliance of Australia and New Zealand (CHAANZ), the Group is creating the National CHD Register to maximise the quality of life for CHD patients by providing the best of care for their life journey, by identifying deadly gaps in the healthcare system. This will be the largest compiled database on CHD in the world and the only resource of its type in Australia.

The Group is also conducting the world’s first randomised controlled study into the benefits of exercise for people with CHD. This information will then be used to develop guidance that can be rolled out across all corners of Australia via hospitals and telehealth services – including to remote areas and Indigenous populations that are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease.